Ramblings: Between the Ears

Some topics for the Tenth Walk, Llanymynech to River Morda, the quarry way, 9 m

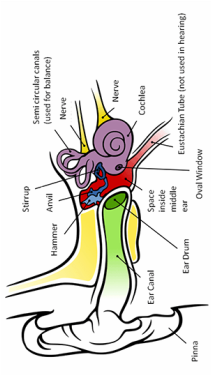

How the Ear Works

The outer ear, the pinna, collects vibrating sound waves and directs them along the ear canal where they encounter the ear drum, a thin, cone-shaped piece of skin about 1 cm wide.

The middle ear, beyond the ear drum, is connected to the throat via the eustachian tube. This connection allows the air pressure on both sides of the eardrum to remain equal. This pressure balance lets your eardrum vibrate freely. The job of the cochlea in the inner ear is to take the physical vibrations and translate them into electrical information that the brain can recognise as sound. It conducts sound through a fluid instead of through air. The small force felt at the eardrum is not strong enough to move this fluid, so before the sound passes on to the cochlea it must be amplified. This is the job of the ossicles, a group of tiny bones in the middle ear. The ossicles are the smallest bones in your body. The organ of corti is a structure containing thousands of tiny hair cells extending across the length of the cochlea. When these hair cells are moved, they generate an electrical current and send it through the cochlea nerve, which is connected to the cochlea itself and on to the cerebral cortex, where they enter the brain. |

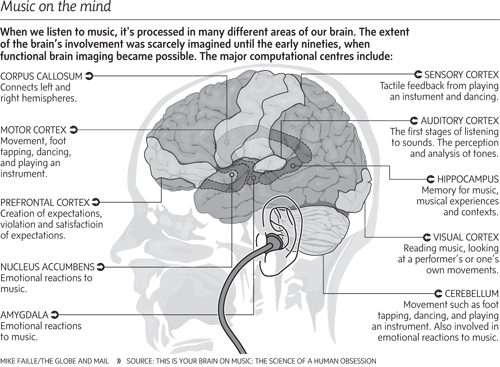

Your Brain Plays Music

When we hear music, information is sent from the cochlea via the brain stem to the primary auditory cortex.

This immediately activates our ‘primitive’ brain, the cerebellum. The ear and the primitive brain are known collectively as the low-level processing units. They perform the main features of extraction which allow the brain to start analysing the sounds. This data is conducted through neurons, cells specialising in transmitting information. The output of these neurons connects to the high-level processing units located in the frontal lobe of the brain. Historical information is stored in configurations of neurons. When a stimulus activates a certain configuration, historical information is retrieved. The high-level processing units construct musical features by constantly referencing historical information coupled with additional stimulus passed on by the low-level processing units. To understand how our brains make music researchers examine these neural configurations or codes. The activation of neurons is called ‘firing’. Firing is an electrical signal that releases chemical substances called neurotransmitters. It is because music triggers these neurotransmitters that it has such a powerful influence over mood states. Sound does not exist outside the brain, where it is simply unconcerned molecules of air moving around. Also, there is no single area of the brain which processes music. Multiple regions of the brain fire upon hearing music: muscular, auditory, visual, linguistic. A consequence is that when some functions of the brain are impaired, for example, in forms of degenerative dementia, subjects may well respond positively to musical stimulii. |

The Unconscious Mind

These descriptions of how the ear works and how the brain makes music are rational, objective and based on empirical observation. This is, of necessity, untainted by speculation, imagination or evangelical religious feelings. In the early development of music history right up until the Renaissance, the opposite was the case. There was no clear separation between art and science when drawing conclusions about the way things work were often what we would now think of as fanciful, or, more politely, imaginative.

The imagination may be a key to understanding what has been lost. In exploring the brain from the perspective not of neurons but of consciousness and self-awareness, the imagination is a tool, even a means of perception. In meditation and dreams, the images and sounds that we perceive can be interpreted as symbols representing inner unconscious processes. Configurations of firing neurons are thus akin to the gods of ancient Greece. The Listening Experience

The listening experience has changed considerably. It has moved from the accompanied poetic recitatives of classical Greece, to court sponsored entertainment and church sponsored worship, to public concerts, thence to recording technology and the reproduction of music at home and finally to .mp3 files and streaming of audio and video on line from anywhere around the world, 24/7.

A listening experience today, as never before, can be lone, isolated and personal, the only visible indication of this might be the presence of tiny in-ear pieces with a couple of wires dangling from them. The lone, personal experience focuses the listener on the music taking place between the ears, isolated from its original source. |

The Power of Music to Heal

|

Website by Weebly